|

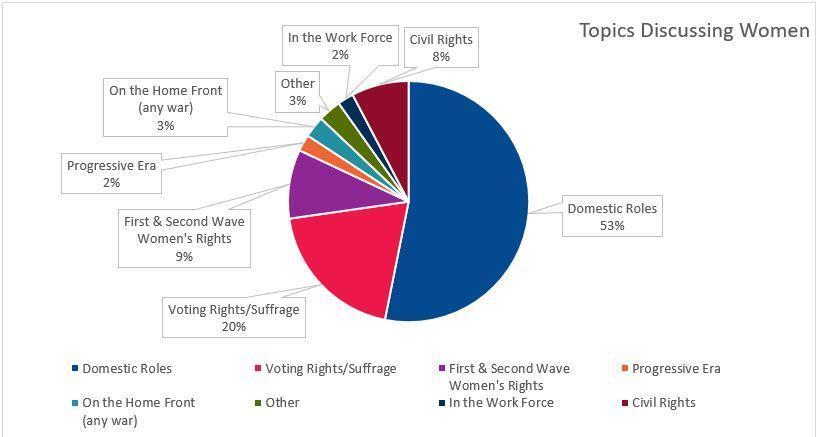

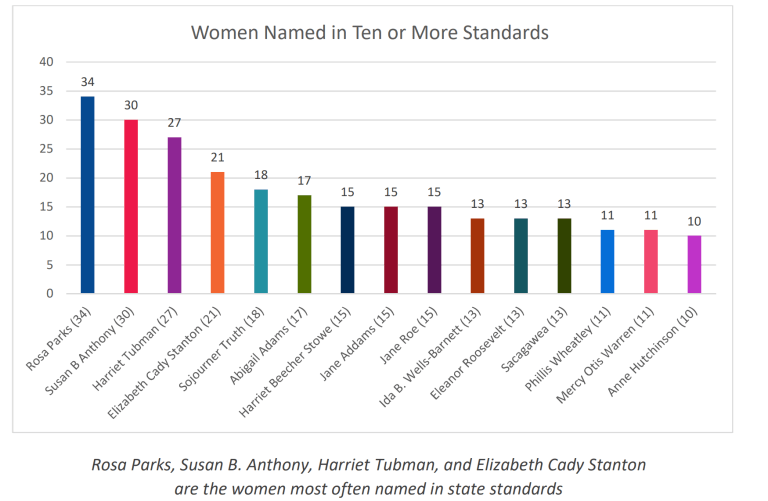

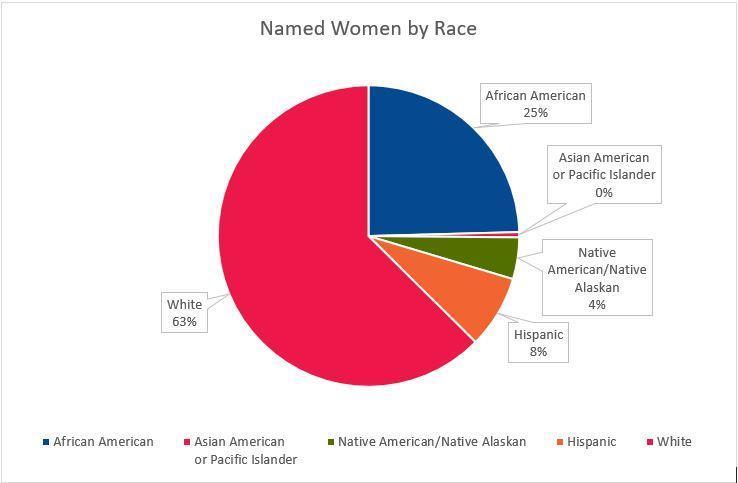

The 2019-2020 academic year marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” So in 1920 white women all over the country could finally vote. Women in Wyoming had been voting since 1869. Black women and other women of color would have to wait until the Voting Rights Acts of the 1960’s, 70’s, and 80’s to exercise that right. National female suffrage, even with significant limitations, in the United States was a huge win for the women’s movement. Any history teacher worth her salt will be sure to mention it this year. Then she’ll get down to the serious work of teaching her students about the past–which, in most classrooms around the United States, means talking almost exclusively about men. In fact, any teacher concerned with her students passing an exam at the end of the year won’t spend very much time on women at all. The tests hardly mention them. (The primacy of standardized tests in education is certainly part of the problem, but that’s an issue for another post.) Take the case of my home state, New York, where half a million high school students sit for social studies Regents exams every June. The US History and Government Regents exam typically includes three to five questions about women. There are usually two on the Global History exam. Both name, on average, one woman per test. “Economics, the Enterprise System, and Finance” never mentions women or gender and includes no material on sexism or racism. The near-absence of women on these tests reflects the lack of women in state learning standards, the guidelines teachers use to design their lessons. The New York State guidelines for grades 9-12 mention “women,” “gender” and the names of individual women about 20 times in total. The most notable gaps are in the twelfth grade courses. “Participation in Government and Civics” addresses gender once, parenthetically: “the degree to which rights extend equally and fairly to all (e.g., race, class, gender, sexual orientation) is a continued source of civic contention.” “Economics, the Enterprise System, and Finance” never mentions women or gender and includes no material on sexism or racism, two factors which so often impede women seeking leadership and fair pay. New York’s guidelines are better than those of many other states. The guidelines in North Carolina, Arizona and Illinois never mention women or gender at all. According to a study conducted by the National Women’s History Museum in 2017, when history guidelines do include women, 63% of the time they are white; 53% of the time they are in domestic roles; 2% of the time they are in the workforce. Some states try to cover their bases with a catch-all list. Oregon’s K-12 guidelines remind teachers 16 times to include “individuals from traditionally marginalized groups (women, people with disabilities, immigrants, refugees, and individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender).” Connecticut’s favored list: “various groups including indigenous Americans, various religious groups, women, slaves, and others.” Connecticut’s favored list: “various groups including indigenous Americans, various religious groups, women, slaves, and others.” These lists shunt women and other marginalized groups into a second-class category. They become the side dishes from which you can choose to accompany your main course of white, male history. Rosa Parks is the woman who appears most often in history guidelines around the country. In the context of these catch-all lists and guidelines that otherwise ignore race and gender, her inclusion feels a little bit like a two-for-one special. Textbooks provide little help to busy teachers looking for material. Rather than weaving discussions of gender roles and women into the central narrative, textbooks like the 2009 edition of McDougal Littel’s World History tend to include women in short, separate sections with headings like “women’s roles.” Students are left to wonder if the farmers, artisans, inventors and pioneers in rest of the chapter were all men. Exams, state guidelines, and even textbooks are not the last word in secondary education. Teachers can and do pursue topics beyond their requirements. Private school teachers can ignore them entirely. But these low numbers are a concrete example of a much wider trend: History teachers around the country largely ignore the past of women. In a time when women continue to fight to be taken seriously as leaders, paid equitably and respected in their bodies and minds, we urgently need to teach young people to see women as full and active participants in the human experience. Women’s concerns are human concerns. And human concerns, so often presented as exclusively male or gender-neutral, are women’s concerns: war, money, art, property, representation, achievement, justice and the environment. Understanding women’s past and how gender roles change over time is as much a part of being an educated citizen as the scientific method. We need to teach history so that women’s absence is questioned and explored rather than taken for granted. For example, between the death of Catherine the Great in 1796 and the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, there was not one female head of state in Europe. Victoria of England was a figurehead and had nothing like the political power of say, Elizabeth I. Instead of breezing by this startling 180-year absence, teachers should ask their students, “How and why did the transition to constitutional monarchy lessen European women’s roles in politics?” Asking these kinds of questions will shift students’ mindsets about the nature of power and progress. Still, standardized tests, guidelines and textbooks make it hard to teach about women. What can be done? Rewrite the guidelines and textbooks to include rich material on women. Make sure that the material reflects the diversity of women’s experiences. Asian, black, Latinx, Native American and transgender women’s experiences should be the center of various units of study, rather than add-ons to a narrative about white male progress. Create online databases for teachers. These resources should include both primary and secondary sources: women in their own words as well as women’s stories integrated into larger narratives. Historians and K-12 educators should collaborate to adapt the material that already exists at the university level for younger students. The New York Historical Society’s Center for Women’s History has already created a free curriculum guide for teachers called “Women and the American Story.” Groups like the American History Association and National Women’s Studies Association should build on these efforts. Educate teachers about these resources. Schools of education and mid-career professional development programs should train teachers to discuss women and gender, to dissect notions of masculinity and femininity, and to ask questions about the past that pertain to women’s lives. The stories teachers tell have a way of shaping our perception of the world. A history teacher’s stories are particularly potent because they have, for young people with emerging world views, the weight of truth. We have to stop presenting a picture of the past incomplete to the point of being false. If Americans don’t have context for understanding women in the past, how can we begin to imagine a future of gender equity? Graphs used with the permission of the National Women’s History Museum. For the complete Report on the Status of Women in the United States Social Studies Standards, click here. Want to use this in your class? Download printable PDF

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed